A previous version of this article incorrectly said that Lockheed Martin is partnering with BMX Technologies. The company is BWX Technologies. The article has been corrected.

Lockheed Martin on Wednesday won a contract to build a nuclear thermal rocket engine, a key technology long coveted by both NASA and the Pentagon that could dramatically speed up space travel and help humans get to Mars.

Under the contract, issued by NASA and the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency (DARPA), the Defense Department unit that seeks to develop transformative technologies, Lockheed Martin will work to first fly the engine by 2027. If the company meets all the milestones, including the test flight, it will receive nearly $500 million, with half coming from NASA and half from DARPA.

NASA is keenly interested in nuclear thermal power for missions to Mars. Using today’s chemically fueled rockets, flights to the Red Planet could take seven months or more, potentially exposing astronauts to long periods of radiation. Having humans cooped up in confined spaces for months could also lead to mental health problems and disagreements among crew members.

One of the main challenges of sending humans to Mars is the great distance between the planets. Earth and Mars are only on the same side of the sun every 26 months. But even at their closest points, a spacecraft aiming for Mars would have to follow a long elliptical orbit around the sun totaling hundreds of millions of miles.

“In order for our country, for our species, to further explore space we need changes in more efficient propulsion,” Kirk Shireman, Lockheed Martin’s vice president of lunar exploration campaigns, told reporters Wednesday. “Higher thrust propulsion is really, really important. And I think we’re on the cusp of that here.”

In a statement, NASA said that nuclear propulsion “is a key capability on NASA’s road map to send astronauts to Mars. A nuclear-powered rocket would enable faster trips to the Red Planet, making missions less complex and safer for crew. This type of engine requires significantly less propellant than chemical rockets, so missions would be able to carry additional scientific equipment.”

It also could help with the space agency’s quest to return astronauts to the moon and create a permanent presence there. To meet those goals, SpaceX and Blue Origin, which hold the contracts to develop landers to bring people to the lunar surface, intend to build spacecraft that are capable of being refueled in space.

But nuclear technology could make complicated refueling less necessary to maintain the frequent trips of cargo and supplies NASA anticipates as the U.S. presence on the moon becomes more permanent. NASA hopes to have astronauts on the moon by 2025, but over time it intends to establish bases on the moon as well as a space station that would orbit the moon and serve as a way station for astronauts headed to the lunar surface.

The Pentagon is also interested in more efficient fuel sources for space travel, especially as it seeks to build satellites that can maneuver in space, making them more difficult for adversaries to target. DARPA said the technology would help move “larger payloads into farther locations in cislunar space — the volume of space between the Earth and the moon.” Doing that, it said, “will require a leap-ahead in propulsion technology.”

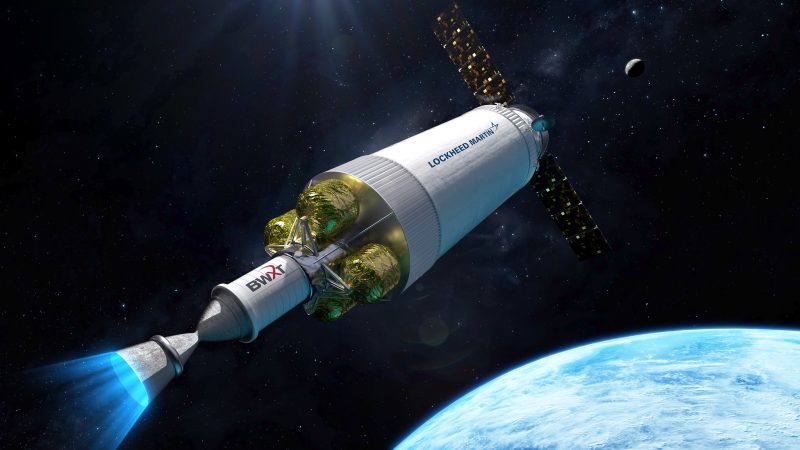

Nuclear thermal power uses a fission-based nuclear reactor to heat hydrogen to an extremely high temperature and then shoot the gas through an engine nozzle to create thrust. Lockheed Martin said that for safety reasons, the reactor would not be turned on until the spacecraft has reached a safe orbit.

Officials said during a briefing Wednesday that the test engine will be launched from Cape Canaveral, Fla., on either SpaceX’s Falcon 9 rocket or the United Launch Alliance’s Vulcan Centaur rocket, the two vehicles with national security launch contracts. Lockheed is partnering with BWX Technologies to develop the reactor and produce the fuel.