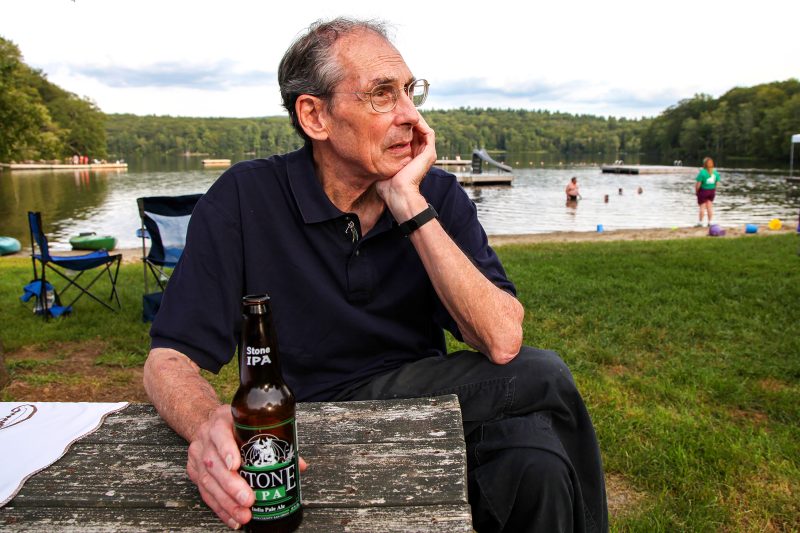

Jerry Doolittle, who wrote White House jokes and murder mysteries, dies at 90

Jerry Doolittle, a onetime Washington Post humorist whose eclectic career took him to Laos as a U.S. press attaché who later helped disclose the full scope of a secret U.S. bombing campaign, and then to the White House as a speechwriter tasked with crafting jokes for President Jimmy Carter, died Nov. 19 at 90.

Mr. Doolittle died of complications from sepsis at a health-care facility in Salisbury, Conn., said his son, Theodore Doolittle.

Trying to define Mr. Doolittle was like trying to hit a moving target. There he was. And then he was on to something else. “I seem to have about a two-year span of attention,” he told a Harvard Crimson reporter in 1986 during a stint teaching expository writing at Harvard University.

His math is about right. He was a study in reinvention. Mr. Doolittle went on to write a series of murder-mystery novels in the 1990s featuring a fictional private eye, Tom Bethany, who keeps true to his progressive politics and sometimes relies on world-class wrestling skills to get what he needs. And did we mention the snakes? Mr. Doolittle was an accomplished amateur herpetologist who never got around to finishing an opus on the snakes of America. (One of the characters in the Bethany series had a 10-foot python named Julius Squeezer.)

“You know what keeps me going?” he said in an interview with Mystery Scene magazine in 2007. “I want to get up in the morning to see what happens next.”

Irreverence was certainly one of Mr. Doolittle’s default settings. At The Post in the early 1960s, he carved out a singular niche. His satirical pieces often took aim at the political phobias of the day.

He mocked the ultraright John Birch Society in 1963 when it advised members on Halloween to give UNICEF trick-or-treaters a denunciation of the United Nations. Mr. Doolittle took on Cold War paranoia with a parody of an intelligence chief ordering the cleaning staff to be put under surveillance as possible defectors.

In a 1962 column skewering not-in-my-backyard zealotry, Mr. Doolittle imagined a zoning fight over the construction of the Taj Mahal. “We’re not against monuments,” Mr. Doolittle had one imaginary taxpayer complaining. “We love monuments in their place, but we just don’t think this is the place for one.”

On the Beatles beat in 1964, when the Fab Four played the Washington Coliseum, Mr. Doolittle described the fans as forming “a twisting, hopping frieze of adulation.”

On another assignment, Mr. Doolittle profiled Leonard Marks, a Washington lawyer about to be appointed director of the now-defunct U.S. Information Agency. Marks offered Mr. Doolittle a position in 1966 as press attaché at the U.S. Embassy in Morocco. His next posting was in 1969 in Vientiane, Laos, during the height of a secret U.S. bombing campaign on suspected North Vietnamese forces and sympathizers in Laos.

As spokesman, Mr. Doolittle was told to stick to the U.S. line that unarmed reconnaissance flights were conducted over Laos and fighter jet escorts occasionally returned fire if under attack. “This was a lie,” Mr. Doolittle later wrote in the New York Times. “Every reporter to whom I told it knew it was a lie. … Every interested Congressman and newspaper reader knew it was a lie.”

President Richard M. Nixon eventually acknowledged the bombing of Laos, but the full details remained withheld from the public. Mr. Doolittle broke ranks and offered off-the-record help to a former Post colleague, Les Whitten, for an account of U.S. bombing raids on a Laotian village while Whitten was doing research for the widely read Jack Anderson column.

The story, which ran in February 1970, brought added pressure on the Nixon administration. Another journalist, Fred Branfman, reported in 1971 on the devastating human toll of the bombings.

“The lies did serve to keep something from somebody, and the somebody was us,” Mr. Doolittle wrote.

Mr. Doolittle resigned from the diplomatic corps in early 1971 and later helped resettle several families from Southeast Asia in the United States, including personally sponsoring a Laotian couple and their two children.

Before he left Laos, however, Mr. Doolittle had to deal with a 15-foot python he bought at a local market. The snake would not eat the live chickens he offered. He ended up packing the python onto his motorcycle and released it into the jungle.

In 1976 — after working on two Time-Life books “Canyons and Mesas” (1974) and “The Southern Appalachians” (1975) — Mr. Doolittle joined the Carter presidential campaign. “I always thought that presidential campaigns were great theater,” he said.

After Carter’s victory, Mr. Doolittle was brought onto the White House speechwriting team. Part of his remit was to inject some levity into Carter’s speeches. It was not an easy fit. Mr. Doolittle complained that the president just did not have natural comic timing and resisted rehearsing the lines.

There were some successes. Mr. Doolittle’s team managed to get in a line about Carter’s colorful and scandal-prone brother, Billy, into a speech the president gave to the Washington Press Club in 1977. Carter described walking up Pennsylvania Avenue after his inauguration.

“I could hear the vast crowd saying, ‘Look, look, look,” Carter said. “And I was feeling very good until they said, ‘There goes Billy’s brother.’”

Jerome Hill Doolittle was born in Pittsburgh on July 15, 1933. In the late 1930s, the family relocated to northwestern Connecticut after his father became headmaster of the Indian Mountain School in Lakeville, Conn.

During World War II — with his father in the military and his mother struggling with ill health — Mr. Doolittle and his siblings spent long stretches at the school and roamed the grounds, where Mr. Doolittle first developed his interest in snakes.

Mr. Doolittle graduated in 1954 from Middlebury College in Vermont, then entered the Army. He often said his experience as an enlisted soldier instilled a lifelong disdain for authority figures.

While writing for a base newspaper, he spelled out an obscene message using the first letters of the words along the left column. He said he was spared a court-martial because of fears by base commanders that he could be related to war hero Lt. Gen. James H. “Jimmy” Doolittle. (He was not.)

During his military service, he married a former Middlebury classmate, Gretchen Dewitt Rath, in 1956. They later moved to Arlington, Va., while Mr. Doolittle began his work at The Post and other newspapers.

After returning from Laos, Mr. Doolittle and his family settled in West Cornwall, Conn. His first novel, “The Bombing Officer” (1982), was highly autobiographical: telling the story of a young American diplomat amid the secret air war in Laos. He taught writing at Harvard from 1985 to 1990.

In addition to his wife, survivors include five sons, Theodore, Timothy, Jonathan, Michael and Matthew; a sister; two brothers; and 12 grandchildren.

After Carter’s 1977 press club speech, Mr. Doolittle was feeling pretty good. The Pennsylvania Avenue joke got in and Carter tossed in a few other cracks written by Mr. Doolittle.

Carter, however, apparently thought the whole thing flopped. The speech draft was sent back to Mr. Doolittle with Carter’s own notes.

“He had written in the margins ‘very poor,’” Mr. Doolittle recalled in an interview in December 1978.

“So with that encouragement,” he deadpanned, “I continued.”