NEW YORK — Donald Trump’s 2016 presidential campaign was repeatedly aided by the National Enquirer, which squelched potentially damaging stories about him and pumped out articles pummeling his rivals, the former boss of the supermarket tabloid testified Tuesday during the ex-president’s trial on charges of falsifying business records.

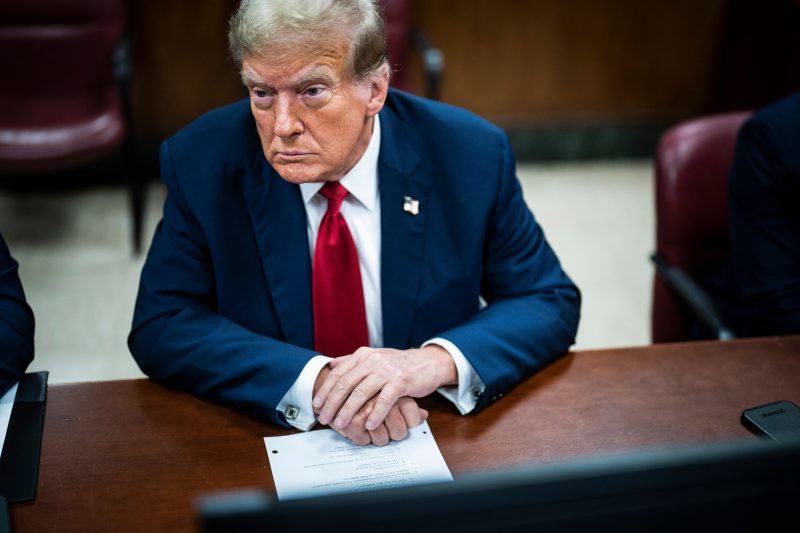

Trump, the first former U.S. president to face a criminal trial, spent his day in the Manhattan courtroom fighting two pitched battles — one against the testimony of former tabloid executive David Pecker, his longtime friend, and another against the increasingly likely prospect that he will be punished by the trial judge for allegedly violating a gag order.

On both fronts, prosecutors seemed to inflict significant damage. At one point, New York Supreme Court Justice Juan Merchan warned Trump lawyer Todd Blanche that he was “losing all credibility.” At another, Trump grimaced and shook his head as Pecker described how he helped kill an allegation — ultimately found to be false — that Trump had a child with a maid at his building.

The busy court day was punctuated by prosecutors detailing the full factual and legal foundation of their case against Trump, one built around a misdemeanor state charge of trying to illegally influence an election.

Pecker, the former CEO of American Media Inc., the company that once ran the Enquirer and other celebrity gossip publications, said he met with Trump and Trump’s then-lawyer Michael Cohen in 2015 to discuss how the tabloid, which had a long relationship with the real estate mogul and reality TV star, could help Trump’s bid for president.

“I said what I would do is I would run or publish positive stories about Mr. Trump, and I would publish negative stories about his opponents,” Pecker testified.

That wasn’t all he pledged to do.

Pecker said he told Trump: “I would be your eyes and ears. … If I hear anything negative about yourself, or if I hear anything about women selling stories, I would notify Michael Cohen as I did over the last several years.”

The deal Pecker described was a mutual back-scratching arrangement in which Cohen would feed stories to the tabloid about Republican rivals like Ted Cruz, and the paper would publish glowing stories about Trump. Pecker said he had a “great relationship” with Trump dating to the late 1980s, but that didn’t seem to be his primary motivation. Stories about the brash celebrity businessman helped sell copies of the tabloid.

“I needed the help,” Pecker said.

Prosecutors used the testimony by Pecker — who appeared cheerful and relaxed, and occasionally laughed as he testified — as a kind of guide into the world of celebrity gossip, backroom dealmaking and Trump’s secret fear that stories about his private life could damage his presidential bid.

Prosecutors say the 34 criminal counts at issue in the case — falsifying business records — grew out of the original idea of the Trump Tower meeting with Pecker: that Trump and his allies would find a way to “catch and kill” bad stories about him to protect him and his campaign.

Trump defense lawyer Emil Bove objected to some of Pecker’s testimony, arguing that the Manhattan district attorney’s office was trying to make legal conduct — meetings and discussions of celebrity gossip stories — sound like a criminal conspiracy, when Trump was not charged with any such conspiracy, and that the events described in testimony so far were not crimes.

Assistant District Attorney Joshua Steinglass said the prosecution’s entire theory “is predicated on the idea that there was a conspiracy to influence the election in 2016,” adding, “Mr. Bove may interpret some of the evidence in a way that’s different from the way that we interpret it.”

Under New York state law, falsifying business records is a misdemeanor, unless it is done to further or conceal another crime. Then it can be charged, as it was in Trump’s case, as a felony. Since indicting Trump, prosecutors have often been vague about what, exactly, was the underlying crime that was allegedly being concealed or furthered.

In court Tuesday, Steinglass said the statute in question is state election law 17-152 — conspiracy to promote or prevent an election. That law makes it a misdemeanor when two or more people “conspire to promote or prevent the election of any person to a public office by unlawful means.”

The defense and the prosecution did agree on one thing: Both sides expect continued disputes at trial over how much testimony about political figures, and political activity, should be presented to the jury. Trump is the likely Republican nominee in the November presidential election.

Manhattan District Attorney Alvin Bragg has charged that Trump falsified business records to conceal a $130,000 payment made ahead of the 2016 presidential election to adult-film actress Stormy Daniels, to prevent her from saying publicly that she had a sexual encounter with Trump years earlier.

Cohen later pleaded guilty in federal court to a campaign finance violation for arranging that payment and later getting reimbursed by Trump. Trump’s lawyers say their client was unaware of the particulars of how Cohen made the payments and was not part of any criminal pact.

Throughout most of the trial Tuesday, Trump was attentive as Pecker described their relationship.

Pecker recalled buying the rights to a doorman’s claim that Trump had a child outside his marriage — a claim that Pecker said was untrue but nevertheless could have damaged Trump’s campaign. The Enquirer paid $30,000 for the tale and kept it quiet until two months after the election, Pecker said.

Pecker is scheduled to be back on the witness stand Thursday — the trial is not in session on Wednesdays — and is expected to describe discussions with Cohen about other potentially scandalous stories involving Trump and women that they tried to keep from becoming public.

Cohen, a disbarred, convicted lawyer and admitted perjurer, is expected to testify in the case, and Trump has spent much of his time out of court publicly denouncing him — despite a gag order issued by Merchan barring him from making comments about witnesses in the case.

The trial resumed Tuesday with a hearing on the prosecutor’s request that Trump be found in contempt for at least 10 violations of the gag order.

Prosecutor Christopher Conroy asked the judge to remind Trump that “incarceration is an option” if he continues to violate the order. Some of the alleged violations occurred in the hallway just steps outside the courtroom.

“His disobedience,” the prosecutor said, “is willful, it is intentional.”

Trump has previously declared that he would be willing to go to jail over the issue of the gag order.

Trump “says whatever he needs to say to get the results that he wants,” Conroy said. “He’s doing everything he can to undermine this process. It has to stop.”

Prosecutors have asked the judge to impose a $1,000-per-violation fine for the statements.

Blanche, Trump’s lawyer, argued against punishing his client, saying he is a presidential candidate who has to be allowed to respond to political attacks, even if those attacks come from Cohen. He also said social media posts that repost what others say are not a violation of the gag order.

Unimpressed, the judge asked what legal precedent he could cite for that argument.

“We don’t have any case law to support that, but it’s just common sense, your honor,” Blanche replied.

As the hearing wore on, Merchan grew more impatient with what he said were Blanche’s vague and nonresponsive answers.

“You’ve presented nothing. I’ve asked you eight or nine times, show me the exact post he is responding to. You’ve been unable to do that even once,” Merchan said.

“Mr. Blanche, you are losing all credibility,” the judge said. “You’re losing all credibility with the court.”