One year after billionaire Elon Musk bought Twitter for $44 billion, aiming to rid it of a “woke mind virus” that he believed was suppressing free speech, the site’s business outlook appears dire.

The number of people actively tweeting has dropped by more than 30 percent, according to previously unreported data obtained by The Washington Post, and the company — which the entrepreneur behind Tesla and SpaceX has renamed X — is hemorrhaging advertisers and revenue, interviews show.

But in at least one respect, Musk has delivered on his original promise: Twitter has become far less “woke.”

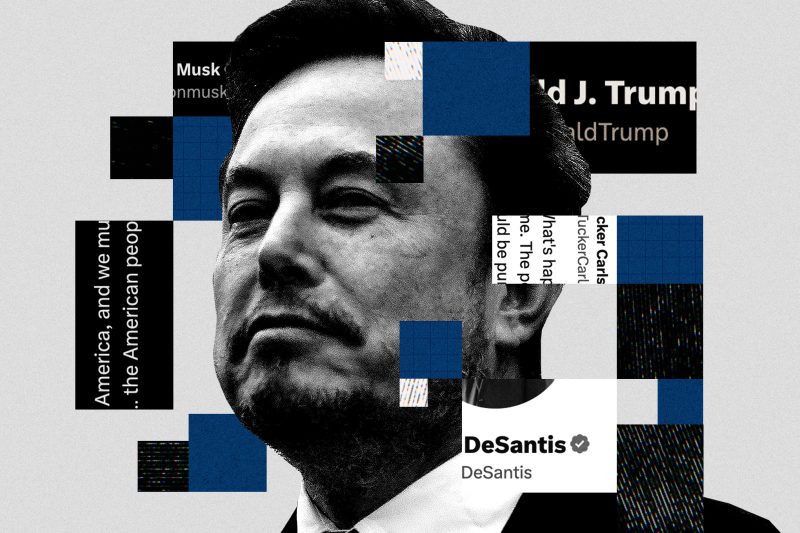

Through dramatic product changes, sudden policy shifts, and his own outsize presence on the platform, Musk has rapidly re-engineered who has a voice on a service that used to be the hub of real-time news and global debate. A site that fueled social movements such as the Arab Spring, Black Lives Matter and #MeToo has veered noticeably rightward under Musk, especially in the United States, say organizers from across the political spectrum.

A Post analysis of dozens of conservative and right-wing influencers and media figures found that many saw their follower counts rise on the day Musk became owner and have continued rising at a rate higher than under Twitter’s previous ownership. None of the dozens of popular liberal and left-wing accounts examined by The Post show the same pattern.

Musk has led Twitter in an explicitly political direction. He publicly endorsed Florida Gov. Ron DeSantis for president and hosted the launch of his campaign for the Republican nomination on Twitter Spaces. He reinstated the account of Donald Trump, who had been permanently banned for his tweets about the Jan. 6, 2021, insurrection.

When Musk hired a new CEO, one of her first moves was to court former Fox News host Tucker Carlson to launch his new program on X, according to people familiar with the matter, who spoke on the condition of anonymity to describe sensitive talks. Carlson and X signed a revenue-sharing deal earlier this month, The Post has learned.

Musk has furthered the company’s rightward turn by displacing the mainstream media from a position of authority on the site: Both X’s software and iconic “blue check” verification system now elevate the tweets of paying subscribers — many of them conservative influencers. People who have worked with Musk and his CEO, Linda Yaccarino, say they intend to turn X into a self-contained forum for creator content where people can watch original shows like Carlson’s.

Amid these shifts, the platform has become a cacophony of misinformation and confusing reports, according to new research from the University of Washington, which found that self-described news aggregators and open-source researchers far outperformed traditional media on the site during the Israel-Gaza war.

“Twitter used to be where politics and news conversations were being shaped on a minute-by-minute basis. I don’t think it’s because I’m a Democrat or on the left — it’s just no longer a place to get accurate information,” said Dan Pfeiffer, the White House communications director under President Barack Obama.

Twitter’s decline has spawned or revived a host of rivals, such as the nonprofit Mastodon and Meta’s Threads. But none has replaced the pivotal role Twitter once played in global debate.

On June 26, Yaccarino, Musk’s handpicked CEO, eagerly welcomed Justin Wells, longtime executive producer for Carlson’s show on Fox News, to talk about a potential partnership, a person familiar with the meeting said.

It was Yaccarino’s first day in the company’s New York offices — her office was festooned with “Welcome Linda” balloons — and she was trying to strike a deal. Forced from his slot as Fox News’s top-rated prime-time host, Carlson had been posting short videos to Twitter for weeks. But Yaccarino wanted to formalize the relationship and share advertising revenue. A Republican who hailed from NBC News, she aimed to recruit top television talent to X — part of an effort to make the platform more like YouTube or TikTok: a hub for original video content.

The talks proved successful, but the broader strategy is a work in progress.

People who have worked with Musk say he isn’t rigidly partisan. He personally contacted former CNN host Don Lemon to talk about providing original content, according to two people familiar with the negotiations who spoke on the condition of anonymity because the talks were private. And X expanded its partnership with NBCUniversal to show live video from the Olympic Games.

But when X launched a revenue-sharing program for creators in July, the roster of initial partners skewed hard right, including self-professed misogynist Andrew Tate, an account called End Wokeness, and several figures who had been banned from Twitter before Musk reinstated them.

Researchers say a broader political shift took shape when Musk began, in April, to dismantle the platform’s system for verifying the authenticity of notable accounts. In its place, Musk installed a new system that allowed anyone to be verified by purchasing an $8-per-month subscription. The company subsequently altered its software to elevate those accounts’ tweets and replies over those of nonpaying users.

Musk got sign-ups for the premium service, first called Twitter Blue and now X Premium, from loyal fans and conservative influencers — almost 1.5 million, although about one-third of those have since canceled, according to Travis Brown, a Berlin software developer who has tracked the site closely. But many news organizations, journalists and liberal public figures decided not to pay. The result was that the platform tilted further right.

“Anyone who pays eight bucks a month, the algorithm now puts their opinions on the top of the news feed,” said Brandon Borrman, Twitter’s former vice president of communications. “And a lot of people who are paying happen to agree with Elon’s worldview.”

Musk quickly came to regard the mainstream media as a rival, if not an enemy, and moved to discourage the use of his site to link to content elsewhere. He routinely exhorts his followers to place their trust in “citizen journalists” who post directly on X rather than professional news organizations. A Post analysis in August found that X was secretly throttling traffic to the New York Times and Facebook, among other sites Musk dislikes. And last month, X stopped displaying the headlines of articles shared on the site, a move he said was “coming from me directly.”

The overall impact of these changes has been to degrade the public’s ability to find authoritative information, according to NewsGuard, a nonpartisan nonprofit that monitors media credibility. That failure has been particularly consequential during the Israel-Gaza war, when Twitter was central to disseminating unproven narratives, such as who blew up a hospital in Gaza.

NewsGuard found that X was a leading purveyor of misinformation in the first weeks of the conflict. And three-fourths of the most viral posts on the platform advancing misinformation came from “verified” accounts, many of them anonymous, the nonprofit concluded.

Ella Irwin, who led Trust and Safety at Twitter under Musk until she left in June, said the verification changes and the removal of headlines from articles risk denting the site’s mass appeal. “If you make it hard for people to … determine how credible content is or where it is coming from, then that really isn’t helping users,” she said. “This could drive users away.”

Musk wasn’t always so partisan. He says he supported Obama, and his business interests in Tesla and SolarCity aligned with liberal support for clean energy subsidies. But he became disenchanted with the left over its criticism of billionaires, support for labor unions, and race and gender politics. As Walter Isaacson detailed in a recent biography, Musk’s child’s transition from male to female, embrace of Marxism and rejection of Musk intensified his visceral resentment of the left.

By 2021, Musk was railing against covid-19 lockdowns and decrying what he called a “woke mind virus” that he argued was threatening the future of civilization. As he spent time on Twitter, he saw symptoms of the “virus” in the social platform’s policies on what it deemed hate speech.

Around that time, Musk began amassing Twitter stock, drawing on his personal fortune to become the company’s largest shareholder.

“Can you buy Twitter and then delete it, please!?” his ex-wife Talulah Riley texted him on March 24, according to text messages released as part of a subsequent lawsuit and reporting by Bloomberg News. Musk’s reply: “Maybe buy it and change it to properly support free speech.” Three weeks later, he offered to purchase the company outright.

Anika Collier Navaroli, a former senior policy official at Twitter who testified last year before the House Jan. 6 committee, said that Musk in many ways is taking Twitter back to its “pre-2016” era, when the site took a laissez-faire approach to moderating user content. “It seems a lot like Elon Musk’s version of free speech was for him and his friends to be able to do hate speech without getting in trouble,” she said.

In a recent talk, Yaccarino claimed Twitter’s business was on the upswing: 90 of Twitter’s top 100 advertisers had returned to the service, and the platform boasted 540 million active users, more than double the 206 million it had in 2021.

“X is a new company building a foundation based on free expression and freedom of speech,” she said.

But now that the company is privately owned and doesn’t have to file reports with the Securities and Exchange Commission, there is scant reliable data about the business. Data obtained by The Post, along with interviews with people familiar with the company’s dealings, contradict Yaccarino’s rosy picture.

“The revenue has not come back, the advertisers have not come back — and a lot of it is Elon,” said a person familiar with the company’s operations, who spoke on the condition of anonymity to describe internal matters. “The math doesn’t add up. I think they are on a very short runway.”

Similarweb, a digital data and analytics company, said global web traffic to X is down 14 percent year over year, and traffic to Twitter’s portal for advertisers, a website that advertisers visit to purchase ads, was down 16.5 percent. And the marketing consulting firm Ebiquity, which works with 70 of the 100 top-spending advertisers in the United States, said this month that just two of its clients are currently advertising on X — down from 31 the month before Musk’s purchase closed.

Twitter’s early woes under Musk were enough to prompt Meta to create a rival service, called Threads, which it developed and launched in just seven months — unusually fast for a brand-new social network from a company of Meta’s size. Mastodon, which launched in 2016, has seen a surge of growth. But none of the rivals yet have been able to replicate Twitter’s impact.

Sarah Oh, a former human rights adviser at Twitter who co-founded a safety-oriented social network, T2, after Musk fired her, said she’s not sure what to make of X’s troubled trajectory: “I’m surprised at the staying power of Twitter,” she said. This week, Oh shut down the site, recently renamed Pebble.

Not everyone is displeased with the direction in which Musk has taken the site.

“Elon Musk has shifted the balance of power” on X, said Christopher Rufo, senior fellow at the conservative Manhattan Institute and a leading crusader against critical race theory, the academic discipline that studies how racism shapes institutions.“Previously it tilted the playing field to the left, and now I think it’s a pretty even split. On a relative basis, this is a huge advantage for the right.”

But even Rufo worries Musk could go too far in his open embrace of the right wing. “If it starts to create the perception that the platform is unbalanced,” he said, “that could diminish its value in the long term.”

Pfeiffer, the former Obama adviser, agreed. “Even if your goal was to change the ideological conversation, you’re less effective because there are fewer people on the platform” he said. “So congrats, Elon, on cutting your nose to spite your face.”