Cannon tells lawyers to weigh if Trump conduct can’t be reviewed by courts

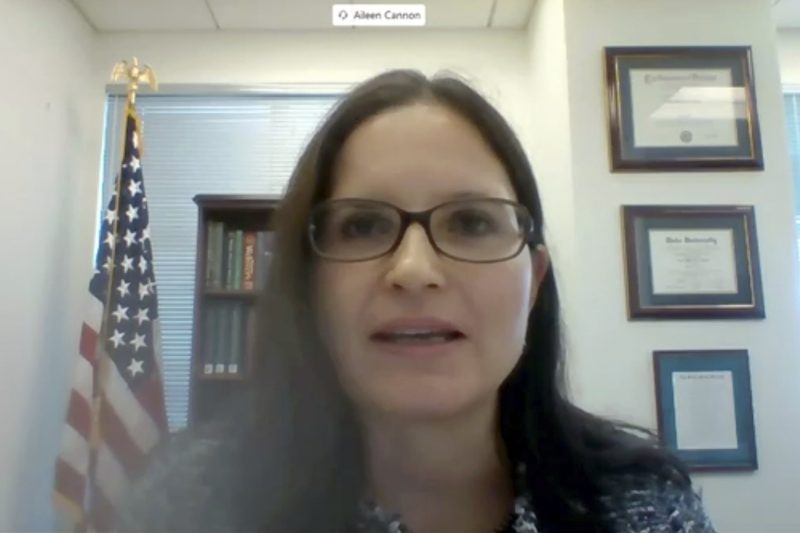

The judge overseeing Donald Trump’s classified-documents case issued an unusual order late Monday regarding jury instructions at the end of the trial — even though she has not yet ruled on when the trial will be held, or a host of other issues.

U.S. District Court Judge Aileen M. Cannon instructed lawyers to file proposed jury instructions by April 2 on two topics that are related to defense motions to have the indictment dismissed outright.

Cannon, a relatively inexperienced judge who was nominated by Trump and has been on the bench since late 2020, listened to arguments about the two defense motions last week.

In that hearing, she sounded skeptical that Trump’s attack on the Espionage Act, or his embrace of the Presidential Records Act, were strong enough to save the former president and likely 2024 Republican White House nominee from a criminal trial. At the same time, she suggested that aspects of Trump’s arguments might be valid enough to come into play during jury instructions.

Juries are instructed on how to weigh the evidence just before they begin deliberating, so Cannon’s focus on this topic suggests she is not only thinking ahead to a trial of the former president, but already zeroing in on the end, rather than the beginning, of such a proceeding.

Her two-page order, however, also suggests an openness to some of the defense’s claims that the Presidential Records Act allows Trump or other presidents to declare highly classified documents to be their own personal property. National security law experts say that is not what the law says, or how it has been interpreted over decades by the courts, particularly given the other laws that govern national security secrets.

Cannon asked the prosecutors and defense attorneys to consider two different hypothetical situations, writing: “the parties must engage with the following competing scenarios and offer alternative draft text that assumes each scenario to be a correct formulation of the law.”

In the first scenario, Cannon said, the jury would be allowed to review a former president’s possession of a record and make a factual finding whether “it is personal or presidential using the definitions set forth in the Presidential Records Act,” also known as the PRA.

Confusingly, she added in a footnote that any “separation of powers or immunity concerns shall be included in this discussion if relevant.” Immunity is a topic for judges to decide, not juries, so it was not immediately clear what that language in Cannon’s order meant.

The second scenario Cannon describes is one in which a president “has sole authority under the PRA to categorize records as personal or presidential during his/her presidency. Neither a court nor a jury is permitted to make or review such a categorization decision.”

That second hypothetical would appear to be one in which Trump seemingly could not be convicted under almost any set of facts of improperly possessing classified documents. It was not immediately clear how Cannon envisions a trial potentially based on that premise.

After the hearing last week, Cannon issued a short order saying that while some of Trump’s arguments about the Espionage Act warrant “serious consideration,” she thought it was too early to dismiss charges based on disagreements over the definition of some terms in the World War I-era law.

At the same time, she suggested Trump could raise the issue later “in connection with jury-instruction briefing and/or other appropriate motions,” an invitation that appears to have led to Monday’s order. Trump had argued in his motion that the Espionage Act, which has been used for decades to convict others of improperly possessing classified documents, was too vaguely worded to be used in his indictment.

Cannon sounded especially doubtful at the hearing of Trump’s other defense claim: that the Presidential Records Act means he could simply declare highly classified documents to be his personal property and keep them at Mar-a-Lago, his Florida home and private club.

The 1978 Presidential Records Act was passed after President Richard M. Nixon sought to destroy White House tapes during the Watergate scandal. It says presidential records belong to the public and are to be turned over to the National Archives and Records Administration at the end of a presidency.

Trump’s Florida case is the first of its kind: a former president charged with dozens of counts of violating national security laws by allegedly stashing classified documents at his home after he left the White House, and then obstructing government efforts to retrieve them.

It is one of four criminal trials Trump is facing, and his lawyers have fought to try to delay them all until after the election. Cannon originally scheduled the Florida trial to begin the week of May 20, but she has made clear more time is needed to sort through pretrial issues having to do with using classified documents as evidence. She held a hearing to discuss a new trial date on March 1 but has not yet ruled.

Trump and his Florida co-defendants also have filed a number of other motions seeking to dismiss the case, including a claim by Trump that he is the target of a vindictive, politically motivated prosecution.

While those motions were not the topic of Cannon’s hearing on Thursday, Trump’s lawyers referred several times during their arguments to other public officials who were not charged after classified documents were found at their homes — including the recent decision by special counsel Robert K. Hur not to charge President Biden.

Those cases, the lawyers argued, show the charges against their client were unjustified and politically motivated.

During the hearing, Cannon questioned several times how prosecutors distinguish Trump’s conduct from that of other former officials. She could schedule additional motion hearings at any time.