Supreme Court skeptical of lawyer’s claim to phrase ‘Trump Too Small’

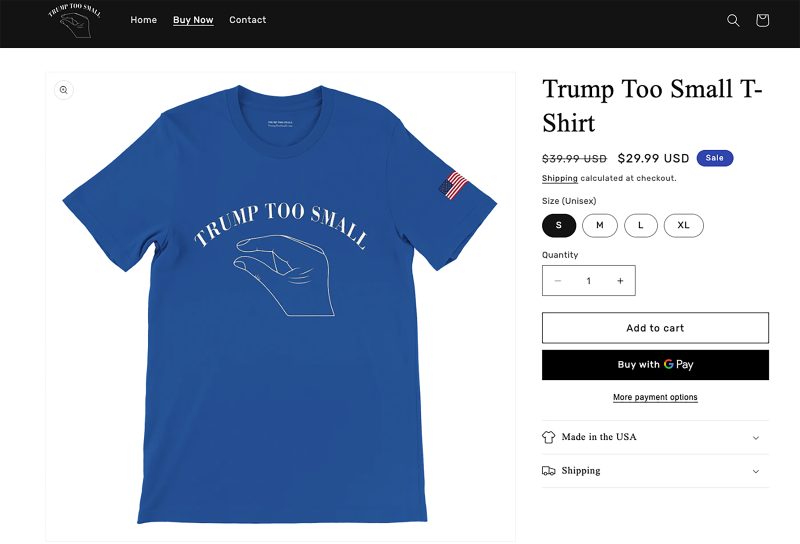

Supreme Court justices across the ideological divide seemed skeptical Wednesday that a California lawyer has a free-speech right to trademark the double-entendre phrase “Trump Too Small” for use on T-shirts criticizing former president Donald Trump.

In fact, Chief Justice John G. Roberts Jr. opined, ruling for Trump critic Steve Elster could make it harder for others to create their own takes about the man running to reclaim his old job.

“Presumably, there will be a race for people to trademark, you know, ‘Trump Too This,’ ‘Trump Too That,’ whatever,” the conservative Roberts told Elster’s lawyer, Jonathan E. Taylor. That could put off-limits political expression “other people might regard as important infringement on their First Amendment rights.”

The debate among the justices mostly concerned how the court could rule for the U.S. Patent and Trade Office — which said Elster’s request violated a law disallowing trademarks that use a person’s name without their consent — but not impose unwanted consequences for other areas of the law, such as copyrights for book titles that use a person’s name.

The bottom line, Justice Sonia Sotomayor said, was that Elster did not suffer an injury when his trademark request was denied.

“The question is, is this an infringement on speech? And the answer is no,” the liberal Sotomayor said, adding that the government is not telling him he can’t use the phrase, just that he can’t trademark it. “There’s no limitation on him selling it. So there’s no traditional infringement.”

Indeed, the shirt is widely available to order on the internet.

The phrase draws from a locker-room taunt during the 2016 presidential campaign. Tired of Trump’s use of “Little Marco,” Sen. Marco Rubio (R-Fla.) mentioned the size of Trump’s hands during a campaign stop.

“You know what they say about men with small hands,” Rubio told a crowd in Salem, Va., in February 2016, pausing to let the audience laugh. “You can’t trust them.”

Trump responded during a televised presidential debate days later with a remarkable claim that drew headlines unseen in any previous presidential campaign.

“Look at those hands, are they small hands?” Trump said, raising them for viewers to see. “And, he referred to my hands — ‘If they’re small, something else must be small.’ I guarantee you there’s no problem. I guarantee.”

Elster wanted to trademark the “Trump Too Small” phrase to criticize the size of Trump’s package of policy proposals. A unanimous panel of the U.S. Court of Appeals for the Federal Circuit ruled in his favor last year, saying the prohibition on violating a person’s privacy was outweighed by Elster’s First Amendment right to criticize public officials.

“The government has no valid publicity interest that could overcome the First Amendment protections afforded to the political criticism embodied in Elster’s mark,” wrote Judge Timothy B. Dyk. “As a result of the President’s status as a public official, and because Elster’s mark communicates his disagreement with and criticism of the then-President’s approach to governance, the government has no interest in disadvantaging Elster’s speech.”

The case is the latest to come before the Supreme Court involving challenges to trademark denials. In each of the previous cases those seeking registration successfully argued that the government was wrong to reject their requests as offensive.

In Matal v. Tam, government officials refused an Asian American band’s request to trademark their name “The Slants,” saying it would violate a ban on disparaging marks. In Iancu v. Brunetti, the trademark office denied registration to clothing company FUCT because of a prohibition on immoral or scandalous marks.

Trump is not a party to the current suit, and his privacy was defended by the Biden administration. Career Justice Department lawyer Malcolm L. Stewart, arguing his 100th case before the court, made the case that a trademark is a benefit awarded by the government, and consent by an individual to use of his or her name is not an undue burden on speech.

“The living-individual clause simply restricts Mr. Elster’s ability to assert exclusive rights in another person’s name,” he said, and is viewpoint-neutral.

Even if the justices seemed generally to think the government should prevail, some looked for an easier way to rule than deciding whether a trademark was a benefit the government was free to restrict.

“The extent of the government’s authority to attach conditions to government benefits is a very difficult area of constitutional law and potentially quite a dangerous one,” said Justice Samuel A. Alito Jr., who had made a similar argument in the court’s previous considerations of trademark law. Perhaps “our precedent should be extended to cover this situation, but this is quite unlike any of the other cases that we have had concerning that.”

Justices Clarence Thomas and Amy Coney Barrett pressed Stewart about how his argument might effect copyright law, which doesn’t require a person’s consent.

“Let’s imagine that there’s a similar restriction for copyright and somebody wants to write a book called ‘Trump Too Small’ that details Trump’s pettiness over the years and just argues that he’s not a fit public official,” said Barrett, who coincidentally was Trump’s third and final appointment to the Supreme Court. “Are you saying,” she asked Stewart, that the government could restrict the author from using Trump’s name?

Stewart said he thought it possible to make distinctions. Copyright law has “historically been viewed as the engine of free expression,” Stewart said, while trademarks have been seen as necessary to “foster the free flow of commerce and to allow consumers to recognize which goods are manufactured by which merchants.”

Barrett did not seem persuaded, but Elster’s lawyer Taylor had the harder outing.

He told the court that the government’s “sole interest” in denying the trademark is “protecting the feelings of famous people. But that is not a legitimate reason to burden protected speech.”

But Thomas pressed Taylor to detail “what speech precisely is being burdened.”

When Taylor said Elster was being denied government protection that is routinely given to others, Sotomayor said he seemed to be making the government’s case that the decision was about a restriction on benefits, not on speech.

After additional questions, Justice Elena Kagan told Taylor she did not want to “badger you or anything.” But she said he had failed to find a case supporting his proposition that when the law does not favor one viewpoint over another, “government cannot make distinctions when government is only giving out a benefit and not restricting any speech.”

The case is Vidal v. Elster.